The shift from in-seat IFE systems to the bring your own device (BYOD) model is far from complete. After all, nearly all widebody aircraft roll off the production line with embedded systems. Still, some industry stakeholders see the next step coming, and sooner than one might think. With the moniker “Bring Your Own Rights” (BYOR) the idea is that not only is the content playing on your personal device but it is streaming over a live connection; it’s not stored data on board the aircraft.

Late last year executives from Thales and SES suggested that such consumption would happen at some point down the line. The recent deal announced by JetBlue and Amazon suggests that “some day” is now and ViaSat will be called upon to support that effort. So, how well will it scale?

Directly addressing the issue, ViaSat CEO Mark Dankberg says:

“JetBlue and Amazon both wanted to see some form of a test flight that would demonstrate that we really could support dozens of simultaneous streaming users on a single airplane. So one day they sent some testers with 30 smartphones, tablets, and kindles of all kinds on one single flight, the length of the East Coast to stress test the Exede [regional Ka-band] service by having all those devices simultaneously streaming video. Well, obviously it worked. And not only that that’s along with the 300 plus other airplanes that flew that day. So, we’re confident no other inflight Wi-Fi could do that even years from now without creating a black hole of bandwidth that would cut off dozens or 100s of other aircraft from getting any service at all.”

I do not doubt the accuracy of the observations from the one test flight. But the plane likely passed through multiple spot beams, not just one. And the 300+ other airplanes were not all flying at the same time, in the same spot beams or even necessarily connected to the same satellite. A single plane flying with a 20% take rate on streaming does not prove that the entire system is ready to scale to full usage.

Don Buchman, ViaSat’s VP for commercial satellites, acknowledges that “streaming puts a lot of stress” on the capacity planning models the company has developed and on which deployed service is based.

Still, he is confident that the BYOR approach to the IFE market – including free inflight connectivity – is “something of value to passengers on JetBlue” and that it is a global trend, not just a local one.

He is also confident that the ViaSat-1 satellite has the bandwidth to support that plan.

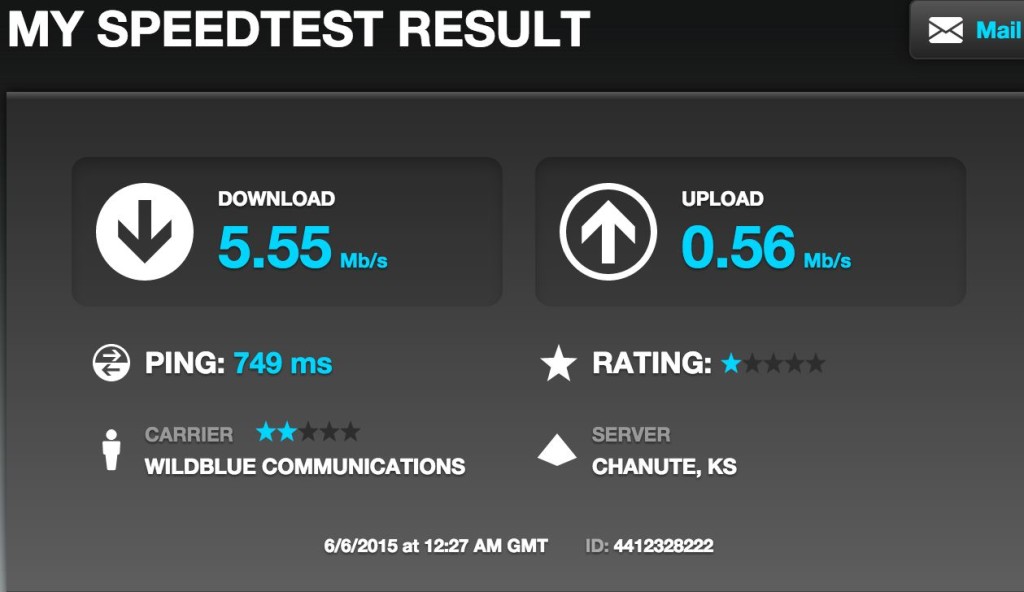

But what about the rest of the country? Currently the Exede product uses ViaSat-1 for service on the east coast. As flights head west the antenna will switch to either WildBlue-1 or the Anik F2 satellites, each of which has significantly lower capacity and many more users in any given coverage area.

The west coast could see coverage shift to ViaSat-1 but a large chunk of the mid-west and mountain states have no upgrade option until ViaSat-2 launches in late 2016. For passengers flying transcon trips – the folks most likely to want to stream a movie to pass the time – that half of the flight runs a much higher risk of insufficient bandwidth on board to support the streaming service.

It is entirely possible that the ViaSat connectivity ecosystem does have sufficient bandwidth to support the inflight demand on top of the terrestrial subscriber base, even as it describes capping growth in certain high demand spot beams. And the majority of flight hours for the system will remain in the shorter-haul markets on the east coast where demand is lower and capacity is higher. But there is still an open question over the rest of the country and the ability of the service to thrive or even survive with high volumes of streaming. We’ll know soon enough how that plays out; the JetBlue/Amazon partnership launches later this year.

But what options are available to airlines that don’t offer an Exede-type connectivity service that can satisfy video streaming? Can they too support BYOR by simply slapping a Neflix or iTunes server, and Wi-Fi network, on board their aircraft? IFE industry veteran Michael Childers insists that this type of scenario would require the on-demand streaming media provider to acquire public performance rights. During the recent APEX Technology Conference in California, Childers said:

“If we are talking about … cached content [on board] that is something that does require licensed rights. The same reason why a VOD Internet-based service provider can’t put a fileserver in a movie theater and say ‘I am not going to share my revenue with the studios anymore, I am simply going to stream Netflix and you bring your iPad and we’ll be fine’. It’s the same reason you cannot do the same thing on a college campus because those are theatrical rights and non-theatrical rights and those are preserved.”

Childers noted, however, that “any content provider could decide at any time that there is enough value in mobility of content” and change their tune for a variety of reasons, including the cost of maintaining the status quo. “[It] could be particularly true if the cost of subtitling, captioning some of those things [for the non-theatrical market] starts to become very costly. It is a content provider decision, it is a contractual decision, but it is not something that we on the technology side of the business can do just because we can and just because we think it is a good idea,” he said.

Featured image credited to Jason Rabinowitz